Knut, Stephanie and Jorunn Clinical trials and patient biopsies

The T cells and B cells that we study at our research centre all come from gut biopsies or blood samples that individuals with coeliac disease donate to research. This is extremely important to ensure that the observations we make are correct and directly disease relevant.

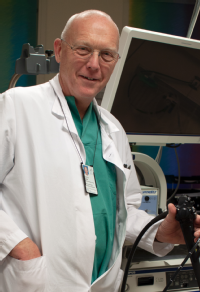

My name is Knut Lundin and I am a clinical gastroenterologist and group leader in JCoDiRC. My medical career started back in 1986 in the lab of professor Erik Thorsby, where I also met Ludvig Sollid. Since then we have worked together on many studies and shared our findings through numerous academic publications. In Norway, most patients with coeliac disease are seen in our public hospitals. I work at Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, where we see the full range of coeliac disease from “regular” to “hard to diagnose” and “complicated” cases.

My name is Knut Lundin and I am a clinical gastroenterologist and group leader in JCoDiRC. My medical career started back in 1986 in the lab of professor Erik Thorsby, where I also met Ludvig Sollid. Since then we have worked together on many studies and shared our findings through numerous academic publications. In Norway, most patients with coeliac disease are seen in our public hospitals. I work at Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, where we see the full range of coeliac disease from “regular” to “hard to diagnose” and “complicated” cases.

I am also a fully trained endoscopist and work with the doctors and nurses in our endoscopy unit. We have two dedicated study nurses and two staff engineers that work in the unit and amongst their everyday work they also support our work with coeliac disease. We also have a dedicated clinical nutrition unit in the same hospital so we offer the full range of clinical services to our patients.

Thanks to the patients

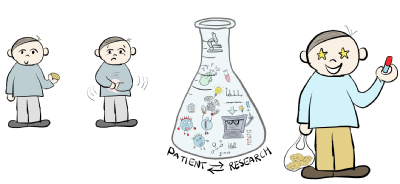

Maybe the most important aspect for our success is the willingness of patients with coeliac disease to provide blood and biopsy samples for research. All patients see our study nurses, receive information and (in almost all cases) agree to take part and sign an informed consent form. Our patients do not only come from regular referrals, but also contact us directly after invitations on social media networks like Facebook.

We also have a formal Clinical Trial Unit. For a number of years now, patients have participated in gluten challenge studies. One of our first examples, was the oat challenge, published in 2003 in Gut, where we described our first oat intolerant patient.

Most of our gluten challenge trials are conducted as part of our translational research projects where we investigate the immune responses in blood and gut during gluten challenge. The long term goal of these trials is, of course, to better understand the disease for the benefit of patients and develop new strategies for diagnosis and treatment.

Most of our gluten challenge trials are conducted as part of our translational research projects where we investigate the immune responses in blood and gut during gluten challenge. The long term goal of these trials is, of course, to better understand the disease for the benefit of patients and develop new strategies for diagnosis and treatment.

We have taken part in several of the most recent industry sponsored drug trials in coeliac disease. The first was a trial of gluten degrading enzymes developed by Alvine Pharmaceuticals, a trial that did not turn out to be as successful as anticipated. We also took part in the Celimune trial for refractory coeliac disease and we are active partners in the ongoing Dr Falk trial, where coeliac disease patients first take a pill and then eat gluten containing cookies for six weeks. The pill inhibits transglutaminase 2 (TG2), an enzyme in the intestine that transforms gluten so it is recognised by the immune system in coeliac disease. This biological function of TG2 was reported from our research back in the 1990s. This shows that “things take time” but also shows the benefit of long term, sustainable scientific effort!

My group also studies non coeliac gluten sensitivity. This research has been possible due to our close collaboration with the clinical nutrition unit, their researchers and clinicians. Our research has shown that in people with non coeliac gluten sensitivity, fructans, as opposed to gluten, may be responsible for people’s symptoms.

It cannot be over emphasised that the most important reason why we succeed with our patient oriented research is the willingness of people with coeliac disease to undergo ongoing biopsy sampling and gluten challenge!

Short term cookie challenge activates T cells

My name is Stephanie Zühlke. I am a medical doctor and PhD student working on gluten specific T cells. As you have heard in the previous days, the gluten specific T cells help to send a message to other cells that gluten is dangerous and must be destroyed.

My name is Stephanie Zühlke. I am a medical doctor and PhD student working on gluten specific T cells. As you have heard in the previous days, the gluten specific T cells help to send a message to other cells that gluten is dangerous and must be destroyed.

We asked people with coeliac disease on a gluten free diet to eat gluten containing cookies for three days. We then monitored the increase in gluten specific T cells in their blood samples. We also tested if only one single gluten containing cookie was sufficient to increase the number of gluten specific T cells in the blood - and one cookie is enough!

But the increase in T cells is not as high after one cookie as it is after three days of gluten cookie challenge. I have focused on refining our knowledge about the profile of the gluten specific T cells. I work with Asbjørn and Louise who presented their research on Monday. More specifically, I look at the expression of surface molecules on the gluten specific T cells once they appear in the blood just after they have been “reactivated” by the gluten challenge. The overall goal is to find good markers that can tell us what makes the gluten specific T cells so special and whether any of the markers can be used to determine if a person with coeliac disease has been exposed to dietary gluten or not.

New method to look for changes in gut tissue

New method to look for changes in gut tissue

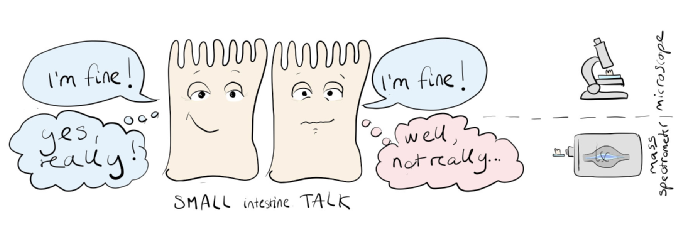

My name is Jorunn Stamnæs. I am a researcher in Ludvig Sollid's group. I’m also the administrative coordinator of the JCoDiRC. I’m currently developing methods to detect changes in the gut that are invisible under the microscope. To diagnose coeliac disease, doctors look at thin slices of gut biopsies under the microscope to judge if it is normal or diseased. Big changes are easy to spot, such as cells that die, change location or size or new cells that arrive. However, many things happen in the tissue that are not visible to the eye.

To study such invisible processes, we look at all the proteins that are present in the tissue both inside and outside the cells. These proteins tell us something about what goes on in the tissue; if all is well or if some or all cells are in a state of alert. We can measure thousands of proteins from just tiny amounts of tissue that we take from the same biopsies slices that the doctors look at under the microscope. To do this we use advanced instruments called mass spectrometers, that in the future, we hope can be connected directly to microscopes. Our method can discover and measure several important invisible changes, and in the future, this approach may be helpful to set the correct diagnosis or to monitor the effect of treatment in cases with no visible changes in the gut.